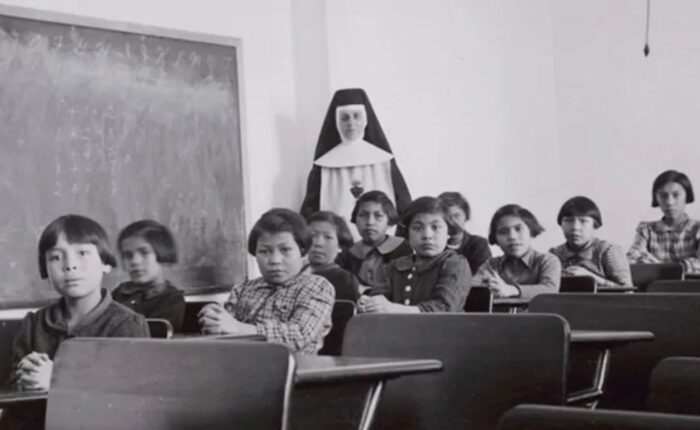

What Happened at Residential Schools

The residential school system can be described as a combination of cultural genocide, psychological, physical and sexual abuse, a place with rampant disease and inadequate healthcare, and overall harsh living conditions with problems linked to the quality of education. These schools operated for over 150 years, with over 150,000 students passing through this system. According to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission chair, over 6000 children died while at the residential schools. The government started funding these schools in the 1880s, while church-funded schools had already been established before. The schools were run by the different denominations: Anglican, Presbyterian, United, and Roman Catholic. The goal of this system was to convert indigenous children to Christianity and assimilate them into mainstream Euro-Canadian Christian society. Attendance was compulsory for all status Indian children. Indigenous children were often forcibly taken from their families and placed in these settings. Many students tried to escape these settings, and the police had to be called to bring them back to the schools. The government started the process of shutting down these schools in the early 1950s and only completed this process in 1996. The different problems of the residential school system are described below.

Cultural Genocide

The overall approach of residential schools was to “kill the Indian in the child”. The approach taught students that indigenous culture in Canada was a primitive savage culture, and schools prohibited students from speaking their mother tongue (even though many children knew no other language) and were punished if they did so. This made it harder for these students to know their culture, traditions, and approach to the world as all of these are closely linked to their indigenous language. The schools did not allow students to practice indigenous culture (eg. such as traditional ceremonies or dances) and forced them to adopt European customs. They were also punished for crying for wanting to return home, and for running away from schools.

According to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, “The distinct cultures, traditions, languages, and knowledge systems of First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples were eroded by forced assimilation” within the schools.

Psychological, Physical, and Sexual Abuse

Students were abused in different ways in the residential schools system for what was considered “misbehaving”.

A recent news article cites the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) report summarizing this torment and says the following:

“The TRC report chronicles barbaric punishments, duly recorded by federal bureaucrats and officials with the churches that ran the schools. Students shackled to one another, placed in handcuffs and leg irons, beaten with sticks and chains, sent to solitary confinement cells for days on end — and schools that knowingly hired convicted “child molesters.” Only a few dozen individuals have ever been prosecuted and convicted for the abuse those children endured.”

In another account, “Survivors recall being beaten and strapped; some students were shackled to their beds; some had needles shoved in their tongues for speaking their native languages.”

Other forms of torment existed in the residential schools. Children, at times, were made to do hard physical labour and were, at other times, deprived of food or made to be part of experiments in malnourishment. Sexual abuse was also reported by many who attended the residential schools.

According to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR), “thousands of students suffered physical and sexual abuse at residential schools. All suffered from loneliness and a longing to be home with their families.” As a result, some committed suicide while others died fleeing their schools.

Disease and Inadequate Healthcare

Disease was highly prevalent in the residential schools system (particularly in the early decades of the system).

Recent research into health concerns at residential schools state that “conditions in the schools were such that disease and death among the children was unmanageable and included the spread of smallpox, measles, influenza and TB” and that “The historical records support many missed opportunities to intervene, and a general apathy to the wellness of these children.”

Reasons for disease (specifically Tuberculosis) were documented by Dr Peter Henderson Bryce, the Chief Medical Officer of Health for the Department of Indian Affairs in the early twentieth century. Reasons he cited are below:

1) Many facilities were re-purposed buildings featuring poor ventilation

2) The schools were overcrowded

3) Minimal efforts were undertaken to isolate sick children and staff

4) Children, already at increased risk for progression to disease, were rendered yet more vulnerable by stress and malnourishment

5) There was limited access to medical care for TB screening or management of other viral illnesses

In addition, research has stated that:

6) Children who were already ill should not have been admitted, but may have been to reach enrolment quotas (as funding to the schools was on a per student basis)

7) Food was withheld as a punishment, resulting in malnutrition/undernourishment

8) Stress was induced due to dislocation from family and home; forbidding the use of indigenous languages, cultural practices, and religious practices; abusive punishments and practices

The same research also has stated the following:

“an overall TB mortality rate of 8,000/100,000 population in the residential school system was seen in the 1930s compared to rates of 51–79/100,000 population in the country overall for the same decade”, as a result of the lack of willingness to take action based on the findings of Dr. Bryce.

Dr. Bryce released numbers on overall deaths as a result of the residential school system in 1907, where he found “that 24 percent of previously healthy Indigenous children across Canada were dying in residential schools. This figure does not include children who died at home, where they were frequently sent when critically ill. Bryce reported that anywhere from 47 percent (on the Peigan Reserve in Alberta) to 75 percent (from File Hills Boarding School in Saskatchewan) of students discharged from residential schools died shortly after returning home.”

Residentials schools also had a significant impact on the mental health of those who attended. Another recent study (different from the one cited above) states that “among 127 residential school Survivors, all but two suffered from mental health issues such as PTSD, substance abuse disorder, major depression, and dysthymic disorder”.

In addition, this publication cites research that found a link between drinking and drug use to the sexual, physical, emotional, and mental abuse experienced at residential school.

Furthermore, research conducted by University of Toronto public health and anthropology professors has found that “The severe hunger and malnutrition that many Indigenous children suffered at Canadian residential schools has contributed to Indigenous peoples’ elevated risk of obesity and diabetes”. They state that “for most of the history of the residential school system, Indigenous children were fed poor quality, often rotting food”

Other research has found the intergenerational link when it comes to residential school attendance and health, where on-reserve youth between the ages of 12 to 17 reported increased suicidal thoughts if they had at least one parent who attended residential school.

Quality of Education

The quality of education was affected by the idea that indigenous students should only do certain tasks, and in addition, schools were underfunded. Girls focused on domestic service and were taught to do laundry, sew, cook, and clean, while boys were taught carpentry, tinsmithing, and farming. In addition, most students only reached grade five at the age of 18 (for a significant period of the residential school system’s history), and at this point, students were sent away. Many were discouraged from pursuing further education.

Next Steps

The legacy of the residential school system is very much in place as a result of the intergenerational link passed down from attendees to their descendants, in addition to the attendees who remain alive. Challenges faced by indigenous people due to this system include involvement in our justice system, over-incarceration, poverty, housing issues such as crowding and poor ventilation, as well as lack of access to clean water and food insecurity, among other factors. The extent of these challenges and tactics to address these challenges will be covered in separate articles.